Working with JSON in PostgreSQL#

As part of a personal project, I wanted to store a large part of the INSEE's french census data in a PostgreSQL database with multi-millennial tables. The problem is that, within the same dataset, the fields can change over the years, which makes it impossible to create a fixed table structure. The solution? Use semi-structured data, i.e. store this data in JSON in a table field. This article is a summary of that experience.

Unscheduled obsolescence

This work was carried out before the release of PostgreSQL 17, which adds important features for JSON with JSON_TABLE, so it won't be mentioned here.

Since we're going to be talking about JSON and semi-structured data, I feel obliged to start this article with a warning.

The relational model is good, eat it up, and integrity constraints were invented for good reason.

This article is not intended to be an invitation to go into YOLO mode on data management: “all you have to do is put everything in JSON” (like a vulgar dev who would put everything in MongoDB, as the bad tongues would say).

JSON for beginners#

For those of you unfamiliar with JSON it's a text-based data representation format from JavaScript that works in part on a key:value system that can be seen as a sort of evolution of XML.

No need for quotation marks for numbers:

Values can take two forms:

- either a single value, as in the example above,

- or an array, a list, enclosed in

[], both of which can be combined in a single JSON object.

What we call an object is everything between the {} used to declare it. To make things even more complex, we can nest objects and give you an example that's a little more meaningful than talking about tomatoes and mushrooms:

An example from the Mozilla site, which will give you a better idea. You can also consult the wikipedia article or the infamous specification site.

PostgreSQL's json types#

PostgreSQL is able to store data/objects in json format in fields that are assigned a dedicated type. There are two types, because otherwise it wouldn't be any fun.

-

The

jsontype is there for historical reasons, to allow databases that used this type in the past to function. It stores information in text form, which is not optimized for a computer. There is, however, an advantage to using it: it allows you to retrieve information on key order. If it's important for you to know thatnameis key 1 andfirstnameis key 2, without having to go through the key name again, then you'll need to use thejsontype. -

the

jsonbtype. The modern type. It stores information in binary form and offers a lot of functions in addition to those of thejsontype.

Indexes#

It is possible to index a json / jsonb field on its first-level keys, and this is done with GIN type indexes:

To index “deeper” values, you'll need to use functional indexes, indexes on functions:

We'll explain this -> later.

For the adventurous, there's a PostgreSQL extension called btree_gin that allows you to create multi-field indexes mixing classic and json fields. It's available natively when you install PostgreSQL, and won't require you to become a C/C++ developer⸱se to install it (hello parquet FDW ! How's it going over there?).

Table creation#

I'm not going to spam you with Data Definition Language, but you can find the complete database schema here.

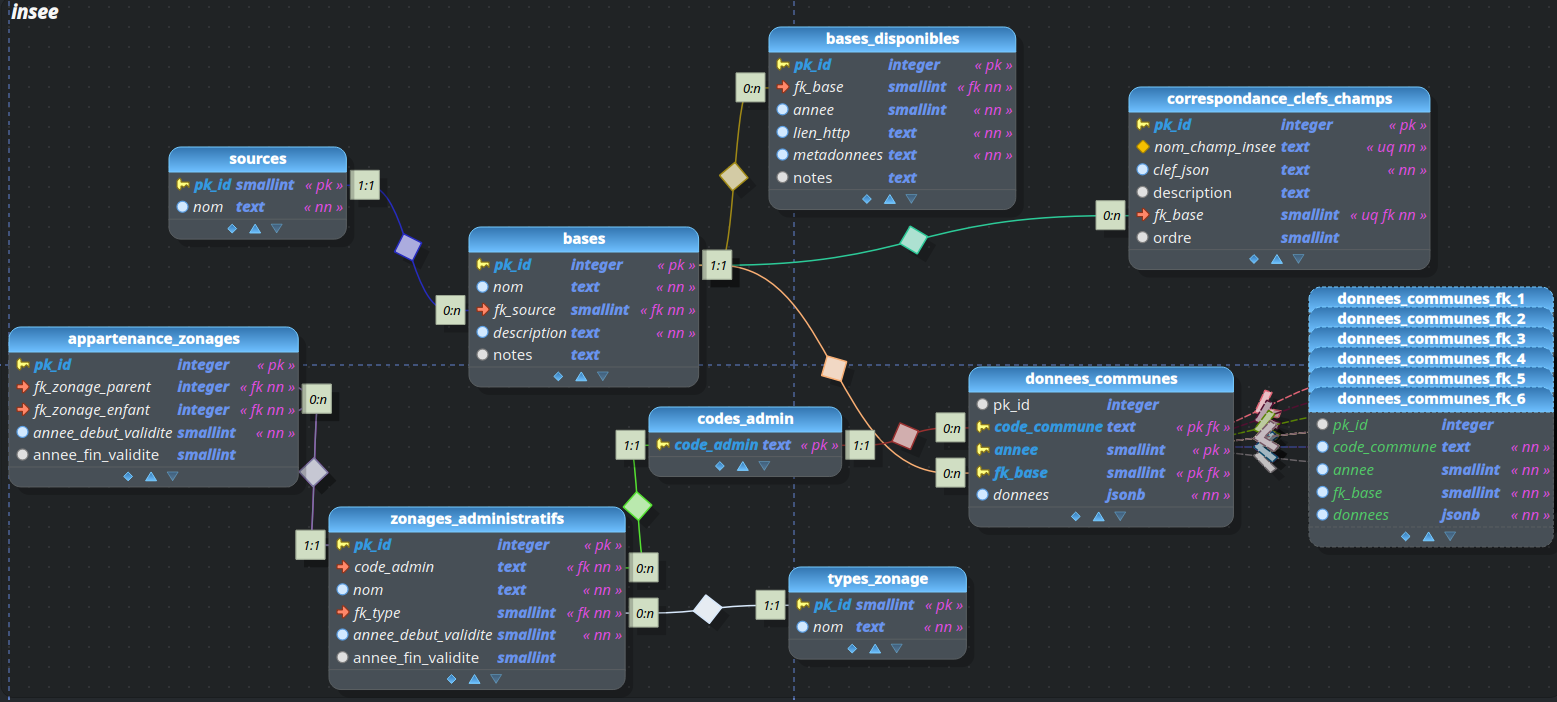

However, here's a brief diagram to help you understand the rest of the article:

*Don't worry about the stacked tables on the right, they're partitions of the donnees_communes table. We won't go into them here, and they're only needed for the example.

Starting from a schema named insee, we'll create two tables:

- the first will contain the list of available bases, the various census components ;

- the second will store the data.

To keep the focus on JSON, we'll spare ourselves 95% of the underlying model. So we won't be handling commune codes, etc. :

The most fussy of you DBAs will have noticed this CHECK. “Why doesn't he use varchar(5)? It really doesn't make sense!” Quite simply, because this form allows you to use a text type with really arbitrary numbers of characters (the text type) unlike varchar(255), while being able to control the minimum and maximum number with the CHECK predicate (unlike varchar which only controls the maximum) as explained on the [Postgres wiki].(https://wiki.postgresql.org/wiki/Don%27t_Do_This#Don.27t_use_varchar.28n.29_by_default).

And we insert a few rows in our insee.bases table :

| SQL script for data insertion | |

|---|---|

Data insertion and retrieval#

To pass text/SQL data to JSON-encoded data in the appropriate dedicated field, PostgreSQL has some functions. We're going to use the jsonb_object() function, which transforms a sql array in the form key1, value1, key2, value2 .... into a jsonb object with only one nesting level. Other functions are available for more complex objects (such as jsonb_build_object()).

Simple example#

We'll create a text string containing the contents of our json, whose values will be separated by commas key1, value1, key2, value2. This string will be passed to a string_to_array() function, transforming it into an array with , as separator to separate the elements of the text string into list elements, a character passed as the function's second parameter. This array will then be sent to the jsonb_object() function.

INSERT INTO insee.donnees_communes (code_commune, annee, fk_base, donnees) VALUES

(

'99999',

2024,

1,

jsonb_object(

string_to_array('tomatoes,42,melons,12',',')

)

)

This request will encode this json object in the data field:

Now how do we get our number of melons for the municipalitie code 99999 in 2024? This is done using special operators:

jsonb_field -> 'key'retrieves the value of a key while preserving its json typejsonb_field ->> 'key'does the same, transforming the value into a “classic” sql type

SELECT

(donnees ->> 'melons')::int4 AS nb_melons

FROM insee.donnees_communes

WHERE

donnees ? 'melons'

AND code_commune = '99999'

AND annee = 2024

You can see that I'm using the ? operator, which is only valid for jsonb fields and not for simple json fields. This is because, when a json/jsonb field is queried, all the records in the table are returned, even those that don't contain the key. So if your table contains 100,000 records, but only 100 contain the key “melons”, not specifying this WHERE clause would return 100,000 rows, 99,900 of which would be NULL.? is a json operator used to ask the question “Is the key present at the first level of the json field for this record?”, and we'd only get our 100 records containing the key “melons”.

If you're still here, I assume you already know this. However, the form (something)::(type) is a PostgreSQL shortcut for making a cast, i.e. converting a value into another type. With ->> the value is returned to us as text and we convert it into an integer.

With nested JSON#

Well, he's a nice guy, but his JSON is still JSON where everything is on the first level. Well, for my needs, that was enough. But I'm not going to run away from my responsibilities and we'll see how it goes with more complex JSON.

I'll use the example from the previous section to make things more complex after this aside.

To inject complex json into a field, we have two solutions: nesting dedicated functions, or castering a text string. Let's imagine a “test” table, in a “test” schema, with a jsonb field named “donnees”.

INSERT INTO test.test (donnees) VALUES

(jsonb_object(

'key1', 'value1',

'key2', jsonb_array(

'foo', 'bar', 'baz')

)

)

This insertion could just as easily be written as a cast from a text string to jsonb. Please note that the json syntax must be respected here:

Data recovery#

To retrieve a value, we use the jsonb_path_query() function, which has two parameters: the name of the field containing the json data, and the json_path to the value to be retrieved. Let's imagine we want to retrieve the second value in the list contained in “key2” :

The $ indicates the start of the returned json path. We follow this first symbol with a dot to move on to the next object. Then, by the next key name and so on up to the searched key, to which we paste a [1] for the 2ᵉ value in the list (values start at 0).

For more information on json_path, please refer to the documentation.

Let's tackle the census#

Well, now that we've tried to explain the concepts as best we can with simple examples, because we've got to start somewhere, let's try something a little more voluminous.

Let's retrieve the latest population data from the municipal census in csv format from the Insee website (you'll want the bases for the main indicators, sorry page not available in english). For this example, we'll use the “Evolution et structure de la population” file. First, clean up the field names. Insee systematically indicates the year in its field names, which means that they change every year for the same indicator.

All field names begin with P or C, indicating main survey (raw answers to census questions) or complementary survey (cross-referencing of answers to establish an indicator). Fields from the main survey and those from the complementary survey must not be cross-referenced. This information should obviously be kept, but for personal reasons, I prefer to put it at the end of the name rather than at the beginning. In this way, we move from normalized fields such as P18_POP to a normalization of this type POP_P.

You'll find here a spreadsheet to take care of all this.

Before inserting the data into our table, we'll go through a temporary table to make the data accessible in Postgres. Using Postgresql's COPY would be tedious, as you'd have to specify the hundred or so fields contained in the census population section of the command. And I'm not ashamed to say that I've got a baobab in my hand at the thought. So we pull out this wonderful software called QGIS. We activate the Explorer and Explorer2 panels. We create a connection to the database with creation rights, and with a graceful flick of the wrist, we drag the file from the Explorer panel to the Postgres database in Explorer2. Let the magic happen.

Now, get ready for perhaps one of the weirdest INSERTs of your life (at least, it was for me!). Ugh. I realize that if I wanted to do this right, I'd also have to explain CTE. But I'll let you click on the link so as not to make it too long.

We're going to use the CTE to concatenate the name we want to give to our keys with the values contained in our temporary table in a string separated by ,. We'll send it to a string_to_array() function and then to a jsonb_object() function. We'll also take the opportunity to clean up any tabs or carriage returns that might remain with a regular expression, using the regex_replace() function. (These characters are called \t,\nand \r). The latter function takes 3 arguments: the source string, the searched-for pattern and the replacement text. The optional g flag* is added to replace all occurrences found.

Note that if your temporary table has a name other than “rp_population_import”, you'll need to modify the FROM clause in the CTE.

| The weirdest INSERT of your life (with a CTE) | |

|---|---|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 | |

Wow.

Be sure to group the inserts in this order: year/base/commune_code, to make it easier for PostgreSQL to read the data.

Now, imagine that, like the author of these lines, your fat, pudgy fingers stumble and slip on your keyboard while writing this query, that a typo slips in, and then it's drama. How do you change the name of a key already encoded in the table? Here's how:

CREATE TABLE example(id int PRIMARY KEY, champ jsonb);

INSERT INTO example VALUES

(1, '{"nme": "test"}'),

(2, '{"nme": "second test"}');

UPDATE example

SET champ = champ - 'nme' || jsonb_build_object('name', champ -> 'nme')

WHERE champ ? 'nme'

returning *;

- is an operator used to remove a key from a json object. For our UPDATE, we therefore remove our typo from the entire object. In addition, we concatenate everything else with the construction of a new object in which we correct the key name. We also assign the value of the key being deleted, which is still usable at UPDATE time, to the fields that originally contained it with ?.

Now what ? What do we do with this ?#

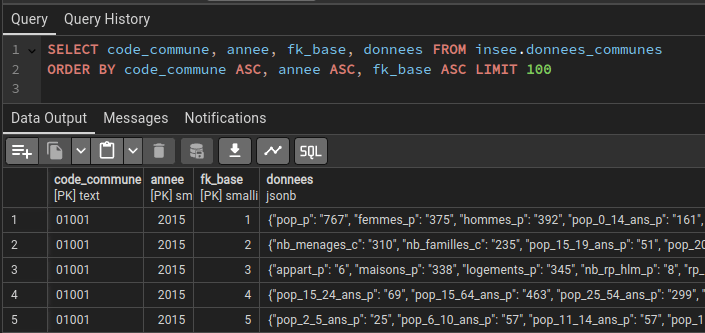

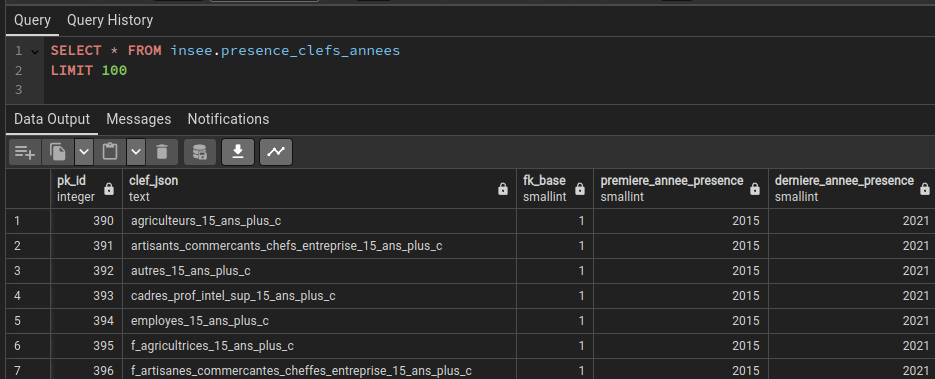

So far, we've only worked with the population component for its latest version. Let's now imagine that we repeat the exercise for all 6 sections and over several years, bearing in mind that over time, certain fields may appear or disappear; changes in the levels of diplomas observed, for example. It would be interesting to retrieve a table showing the first and last year of presence of each key. Let's just say that during this work, we took the opportunity to update a “correspondance_clefs_champs” table listing each key present and its original INSEE name (at least, the one we had standardized).

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW insee.presence_clefs_annees AS

SELECT

c.pk_id AS pk_id,

c.clef_json AS clef_json,

c.fk_base AS fk_base,

a.premiere AS premiere_annee_presence,

a.derniere AS derniere_annee_presence

FROM insee.correspondance_clefs_champs AS c,

LATERAL (SELECT

min(annee) AS premiere,

max(annee) AS derniere

FROM insee.donnees_communes WHERE fk_base = c.fk_base AND donnees ? c.clef_json) AS a

ORDER BY fk_base, clef_json;

The only difficulty here is the presence of LATERAL. This “word” allows you to use a field from the main query in a subquery placed in a FROM clause. The elements of the subquery will then be evaluated atomically before being joined to the original table. Yes, it's not very easy to explain. Here, the WHERE of the subquery will query the donnees field of the “donnees_communes” table to see if it sees the clef_json (json key) being evaluated in the “correspondance_clefs_champs” table with alias “c”. If so, we take the minimum/maximum value of the year field and attach it to this line and this line only. Then evaluate the following clef_json ... (evaluated atomically)

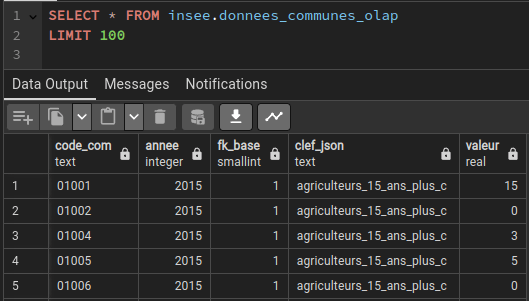

Now we'd like to offer a product that's a little easier to use with all this. Excuse me in advance, I'll copy a 50-line query a second time.

The only table used here that we haven't created is a zonages_administratifs table containing municipalities codes in a code_admin field and a fk_type field containing the type of administrative zoning (1 for municipalities).

Please note that creating or refreshing this materialized view may take some time if you've stored a lot of data (1 hour in my case for the 6 sections from 2015 to 2021).

Finally, in the spirit of living with the times and not like an old cave bear, we're going to convert this materialized view into a parquet file. And for that, we're going to use GDAL, which is truly incredible.

ogr2ogr -of parquet donnees_insee.parquet PG:"dbname='insee' schema='insee' tables='donnees_communes_olap' user='user_name' password='your_password'"

And then you can put the file on a cloud space, like here! You can then get out your best Linkedin publication generator, which will put lots of cute emojis, and show off on social networks (imagine that 90% of Linkedin content has to be made with these things, which are able to generate publications explaining that one of the few advantages of shape over geopackage is that it's a multi-file format, all in a very confident tone).